By Dave Workman

Editor-in-Chief

In the round-gun world, one of the most important things to remember is why they call these handguns “revolvers.”

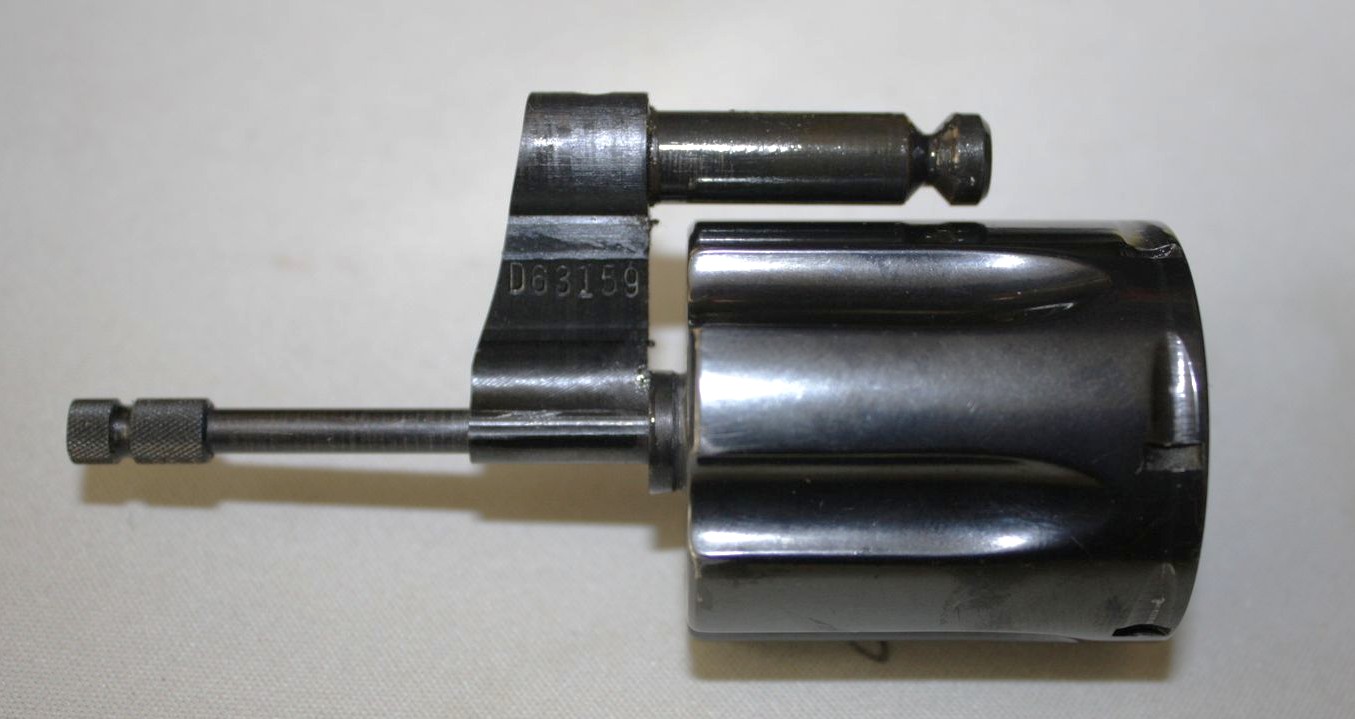

The cylinder—which could also be referred to as a fixed magazine because it isn’t swapped out when all the rounds are fired—revolves, and it does so on a component known alternately known as the “crane” or “yoke” on double-action revolvers with swing-out cylinders. If it is not properly maintained, whether the user doesn’t keep it properly oiled or if it is allowed to build up crud or even rust, due to condensation or simple inattention, your cylinder sill become sluggish at the worst possible moment.

Many people new to wheelgun shooting may not think about proper lubrication and maintenance of the shaft around which the cylinder rotates.

It’s not that difficult to give the crane/yoke a good cleaning, especially with the advent of today’s excellent aerosol cleaners and lubricants. Being from the “old school” of revolvers, however, I prefer to take my sixguns apart to do this little task, because it affords me the chance to actually look the part over, see if or where there is noticeable wear, and if the need arises, drip on a bit of Hoppe’s No. 9 or some other solvent, give it a light brushing with a toothbrush or very light steel wool, wipe off the surface and then add a few drops of light lubricating oil.

I typically give the cylinder a spin after re-mounting it to the crane shaft, to spread the oil evenly around the entire shaft, and the interior surface of the cylinder main shaft.

If your gun is a single-action, just pull the cylinder, wipe off the pin, re-lube it with oil, and reinstall the cylinder.

Trust me on this: Keeping your revolver crane properly lubricated is just as important as adding oil to the slide rail of your semi-auto pistol, since it accomplishes essentially the same task. Cleaning and lubricating metal surfaces exposed to wear will keep your handgun working properly, especially in an emergency situation.

As one might guess from looking at the accompanying images, I’m guilty of shooting revolvers the year around, whether it’s in the blazing heat of an early June long range handgun shoot in eastern Washington, or a trek to the high country for a combination target shoot and small game hunt in mid-winter.

If you camp during the hunting season and keep your revolver close at hand, you will notice each morning that condensation accumulates on the metal. Wiping the gun down removes this from the outer surface, but the same condensation might have formed on some inner surfaces. Mixed with any powder residue which may be present—and this stuff can creep into the action or be on the crane surface—can create a layer of crud which will be noticeable when you cock your revolver. If you need to apply extra pressure to make the cylinder rotate, that’s a red flag warning it is time to disassemble and give your revolver a complete cleaning.

The gun in most of these images is familiar to TGM readers. It’s my classic Colt Diamondback in .38 Special, and with the proper handloads consisting either of a 110- or 125-grain JHP ahead of a charge of either Hodgdon’s HP-38 or CFE Pistol, it is capable of giving a permanent headache to cottontail rabbits or snowshoe hares, and it delivers equal terminal performance on coyotes.

But it won’t deliver the goods unless the handgun in which it is loaded is up to the challenge. Lube that cylinder and crane on a regular basis, and your wheelgun will continue functioning under all kinds of conditions.